Crowe is not surprised by the lines or the videos of farmers throwing away milk and vegetables. She traveled the country for years talking about how a lot of the food we grow gets thrown away and does not reach the people who need it the most.

In 2017, she even created an app so that malls, company cafeterias, restaurants, special events, stadiums and large companies can notify Goodr if they have food for pick up to be donated.

In other words, to make donating food easier.

“Hunger is not a matter of scarcity, but a matter of logistics,” Crowe says often and explained in her 2017 Ted Talk, viewed by almost 1.5 million people.

“There is more than enough food,” she said recently. “There is a social inequity between people who don’t have food and can’t get it and people who have more than they need and throw it away.”

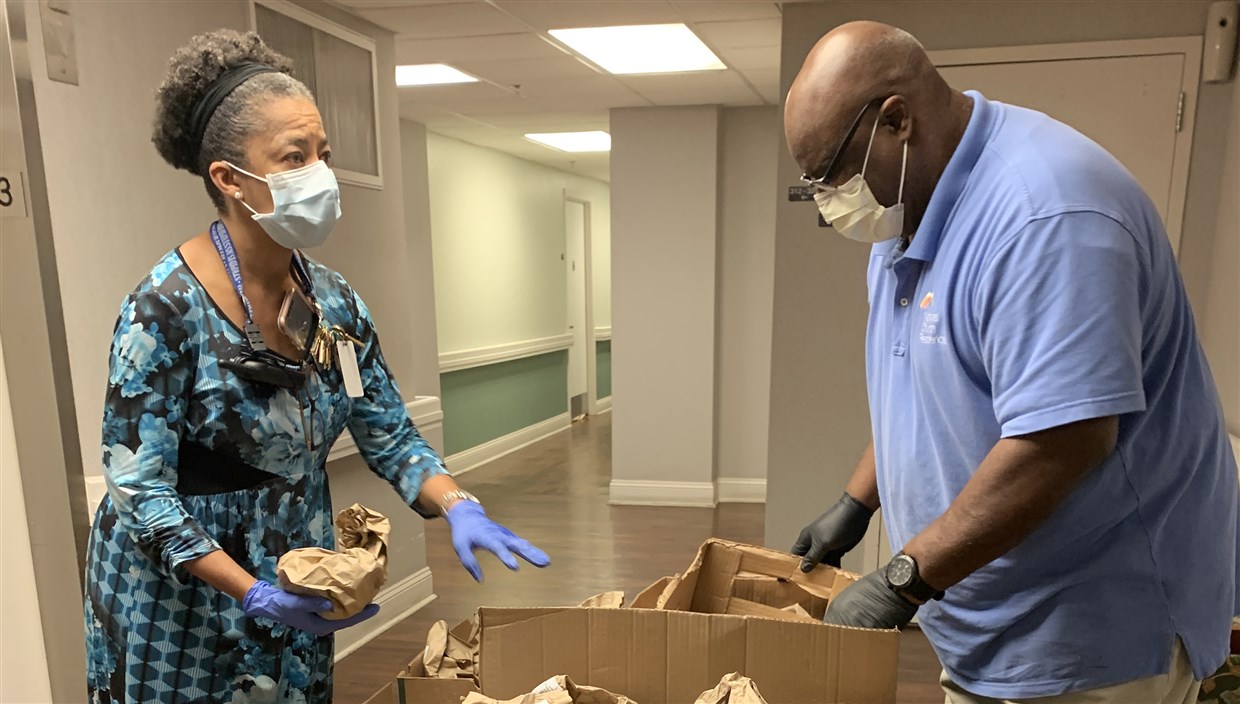

Now in the midst of the pandemic, word of Goodr’s ability to deliver food to vulnerable populations is spreading rapidly.

As part of its community service response to COVID-19, the Atlanta Hawks Foundation partnered with Goodr to provide pop-up grocery markets and food deliveries.

“To date, we’ve supplied over 3,000 families with enough groceries for two weeks with plans to work with Goodr to serve an additional 3,000 families,” said David Lee, Executive Vice President of the Atlanta Hawks and State Farm Arena and Executive Director, Atlanta Hawks Foundation.

“Goodr provided a way for us to assist in sustaining our community during this difficult time.”

According to the United Way, 1 in 8 families — 12.3 percent of all U.S. households — live with hunger. For families in rural areas, 15 percent experience hunger. And 60 percent of households led by older Americans must choose between buying groceries or paying utility bills.

But these are 2019 figures, before the coronavirus pandemic.

Crowe had been convinced for years that technology could solve the problem of addressing hunger: How to have the food industry track and redirect surplus food. She created the answer in 2017 — an app she tailors for each company that partners with her. The app lists a company’s inventory and calculates information such as the weight of the items and the tax value of the donation. Once a company contacts her with a donation list, Goodr contacts a driver to pick up and deliver the food. Goodr even provides the packaging to be used by the company.

In this way, Goodr has diverted nearly 2 million pounds of food from landfills and developed clients that include Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, the NFL and Netflix. Crowe has a staff of 70 employees and operates in seven markets, including Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles.